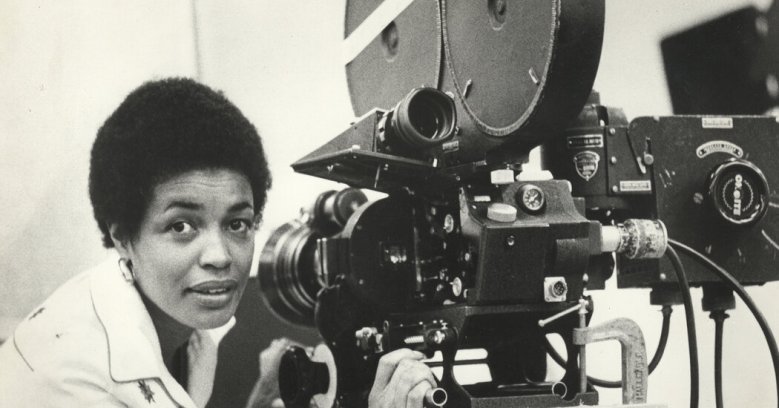

Jessie Maple, Pathbreaking Filmmaker, Is Dead at 86

Jessie Maple, who carved out a career as a camerawoman and independent filmmaker at a time when black women were few in the field, and took great care to follow in her footsteps, May 30. died at his home in Atlanta. She was 86 years old.

Her death was confirmed by E. Daniel Butler, her longtime assistant and co-author of her 2019 self-published memoir, The Maple Crew.

Director and camerawoman are just two of Maple’s many jobs. She also worked as a bacteriologist. She wrote a newspaper column. She owns a coffee shop. Freshly baked vegan cookies. and ran a 50-seat theater in a brownstone basement in Harlem.

When Maple moved from print journalism to broadcast journalism in the early 1970s because she wanted to reach more people, she wrote a column called “Jesse’s Grapevine” for the New York Courier newspaper in Harlem. I was.

After studying film editing under the programs of New York public television station WNET and actor Ossie Davis’ film company Third World Cinema, he worked as an apprentice editor on the Gordon Parkes film Shaft’s Big Score! (1972) and Super Cops (1974), Maple found herself yearning to be behind the camera.

In 1975, she became the first African-American woman to join the New York Cinematographers Guild (now known as the International Guild of Cinematographers), according to Indiana University’s Black Film Center and Archives. her collection of papers and films. However, she said her union banned her after she fought for a rule change that would require her to finish her lengthy apprenticeship.

“If I had waited, I would never have become a photographer,” Maple told The New York Times in a 2016 article about a woman who broke barriers to work as a cinematographer. “So I took them to court.”

She sued several New York television stations for sexism and racism in the mid-1970s and won a lawsuit against WCBS in 1977, earning her a probationary period at the station. It was there that her freelance career blossomed at her local ABC and NBC stations.

Ms. Maple wrote that she faced crew members who didn’t want to work with her and unwelcome whispers behind her back that were sometimes quite audible. But she persevered even when given a task that she found particularly difficult. For example, even though she had motion sickness, she took a helicopter ride almost every day to take aerial shots.

In 1977, Ms. Maple wrote about her experience in How to Become a Union Camerawoman, a detailed guide to success in a banned industry.

But as TV news moved from movies to video, Ms. Maple decided she wanted to be an independent filmmaker with complete control over her work. She worked with her husband Leroy Patton on short documentaries such as “Methadone: Wonder Drugs or Demons?” before she turned to feature films.

Maple said she wants to make films about issues that are important to her community.

“I want to tell stories about things that bother me that might not be told otherwise,” she wrote in her memoir. “I strive to use the resources around me. Most importantly, I strive to be a voice to my employees and the challenges we face. “

Maple is the first African-American woman to produce, write and direct an independent feature film, according to the Black Film Center and Archives. Her film, Will (1981), follows an addiction-stricken ex-college basketball player (played by Obaka Adeduño) who takes in a 12-year-old boy so he doesn’t get into his habit. Loretta Devinein her first film role, playing Will’s lover.

Ms. Maple’s second feature, Twice as Nice (1989), told the story of twin sisters who stand out from college basketball as they prepare to enter the professional draft. The film starred Pamela and Paula McGee, twins who won back-to-back NCAA basketball championships at the University of Southern California but weren’t professional actors.

In 1982, Maple and Patton opened a theater showing “Will” and other independent films in the basement of their brownstone home on 120th Street in Harlem. They called it 20 West, touted it as “the home of black cinema” and featured up-and-coming films like Spike Lee. About a decade later, they closed the film — because she wanted to focus more on her own film, she said.

Ms. Maple’s films have received even higher acclaim in recent years than when they were first released. In 2015, the Museum of Modern Art in New York screened Will. That same year, the Lincoln Center Film Institute (now Films at Lincoln Center) screened both of her films as part of the series Tell It Like It Is: Black Independents in New York, 1968-1986.

Maple was born on February 14, 1937, in Macomb, Michigan, about 130 miles south of Jackson, the second oldest of 12 children. Her father was a farmer and her mother was a teacher and nutritionist.

Her father died when she was 13, and her mother sent her and many of her siblings to the Northeast to attend high school there.

After high school, she studied medical technology and then started working in the field of bacteriology. She ended up running her lab at Manhattan’s Joint Disease Hospital and Medical Center (now part of New York University’s hospital system), but hospital authorities are looking for a permanent replacement. rice field. Because she didn’t have her PhD, she writes. She is credited with leading the preliminary identification of a new species of bacteria. At lunchtime she joined other low-wage workers who were trying to organize.

It was a stable, well-paying job, but Maple, who was married with a young daughter, tired of it and left bacteriology in 1968 to pursue journalism. While she was in Texas on a magazine job, she met Jet and Ebony photographer Patton, who lives in Los Angeles, and forged a cross-coast relationship.

Maple lived separately from her husband. Mr Patton was still living with his wife. Eventually they divorced their spouses and got married, and Mr. Patton moved to Manhattan. (Ms. Maple was sometimes advertised as Jesse Maple Patton in movies.)

Maple has a husband left behind. her daughter, Audrey Snipes; She has five sisters, Lorraine Crosby, Peggy Lincoln, Debbie Reed, Camilla Clark Doremus, and Stephanie Robinson. and her grandchildren.

Maple worked tirelessly to make her dream come true. She supplemented her income through businesses such as her two Harlem coffee shops with Mr. Patton and a series of vegan her cookies made in the 1990s, eventually available at East Coast retailers. It is now possible.

“I was too busy working to slow down,” she wrote in her memoir. “I want to believe that my efforts have paved the way for people behind me to work just as hard, but with a little less pain.”