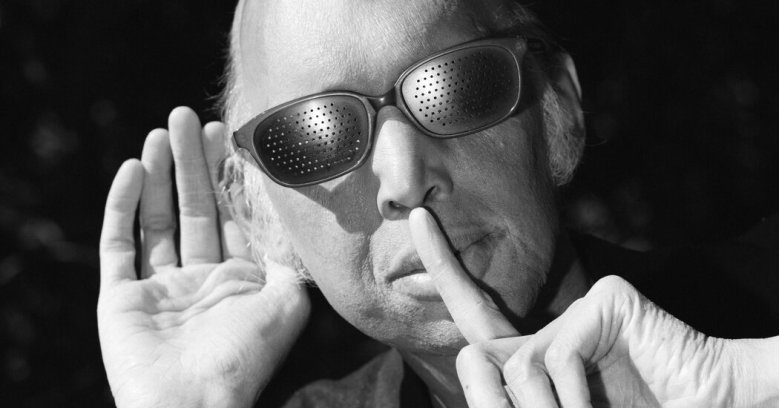

How Shahzad Ismaily Became Musicians’ Favorite Musician

Shahzad Ismaili cannot regulate his body temperature. He was born with no sweat glands, or at least very few sweat glands.

When he was one month old, his parents took him to the hospital because he had a rising fever and beyond breathing difficulties. They found out their only child had ectodermal dysplasia. It is a rare genetic disorder that causes abnormalities in body surfaces such as nails and teeth. Fifty years later, Ismaily has become one of music’s most in-demand collaborators, translating genres like honeyed folk, rambunctious free jazz, and ethereal meditations sung in Urdu like mischievous butterflies. flying around He does not consider these facts irrelevant.

“Since I am very sensitive to the temperature of the outside world, is it possible that I am particularly sensitive to temperature?” condition the world around me In one of several long-term interviews recently, 51-year-old Ismaily was briefly warming himself in the bedside bathtub of his hotel room when he received a call from a tour destination in Holland wondering: rice field. “The most difficult part of playing music with people is a kind of non-verbal and fully empathic perception of how other people are feeling and how the room is feeling. I move with the world around me.I am not a sealed object.”

Ismaily has never released a solo album, but since moving to New York in February 2000, he has performed or produced nearly 400 records, including works by Bonnie “Prince” Billy and Yoko Ono. I’ve been his Brooklyn studio, Figure 8has remained an affordable and comprehensive hub for experimental musicians long after Ismaily became a renowned session player.

This year alone, his delicate keyboards lit up the dark corners of Feist’s “Multitudes.” His bouncy bass provided a combustible substance on Ceramic Dog’s rock record “Connection,” a trio with iconoclastic guitarist Marc Ribot.And his prismatic keyboard and ascanthic rhythms take shape “Love in Exile” The acclaimed debut from the improv group with singer Arouj Aftab and pianist Vijay Iyer. But summing up exactly what Ismaily does, much less how he excels at it, can feel like bottling the wind.

Soft-voiced singer Sam Amidon, who has worked with Ismaily for nearly 20 years, said over the phone, “If you listen to my last record, you won’t realize he’s on it, because he’s the most It’s because I’m not a musician who lives a life.” “But he was bringing out the most beautiful things in other people through his energy every moment he was in the room. there is“

For Ismaily, the invitation to play may be the most important thing. “Since I turned 30, I’ve been asked to walk into a room and be myself musically. It’s been incredibly intense and a very lucky situation,” he said. “My favorite way to work is to walk into a room and have a gut feeling of what to do today.”

For Ismaily, the confidence to play his role didn’t come easily. Shortly after his early emergency room visit, surgeons split his prematurely fused skull to add space to expand with age. The scar runs horizontally across his head, a reminder of his frail health as a child. Due to severe allergies and asthma, he would often wake up panicking on his next breath. For several months he went blind.

When Ismailie was four years old, his mother became a psychiatrist in Pennsylvania, and the family hopped between psychiatric hospital campuses, staying for years at a time. Ismaily quickly learned not only to live with people whose worldviews he did not understand, but to communicate with them and get a glimpse of their reality. He befriended bipolar, depressed and manic patients.

But for a lanky Pakistani boy in a small town in Pennsylvania, who he said had “very thin hair, no teeth, or only one tooth or false teeth, and a squeezed head,” Friends of the same age were much more difficult. Children teased him about why he dresses up for Halloween all year round. His mother worked long hours on the hospital grounds, and his father battled cancer when Ismailie was three years old, making him mentally withdrawn. Left alone, Ismaily slips into the apocalyptic escapades of science fiction, especially Terry Brooks’ Shanara. series. These books taught him to drift beyond his physical environment into another realm.

“People jump straight into it when something they love appears in front of them,” he said.

Music quickly revealed the world he had spent his life exploring. His house was very quiet, with no musical instruments or even a stereo. Yet when Ismaily was two years old, he began to crave the act of making sounds. He especially wanted rhythm, banging spoons against hot radiator coils until his parents broke down and bought him a tiny Muppet. drum kit. The high school marching band was his only source of childhood friends and gave him a respite from judgment.

He set off on a life-saving mission at the Bard College in Simon’s Rock, Massachusetts, which he called “a school of misfits with 300 oddballs.” He joined his friend’s band and eventually left for Arizona to study biochemistry. He was too busy playing music to attend classes and he dropped out one credit short of his master’s degree. While playing in a band there, he found he could get enough shows to pay a meager living. But realizing the same scenario in New York presented new challenges, and Ismaily filled all his ostensible holidays with additional recordings of his sessions and his one-off concerts. Overcommitment kept him afloat. It also cost him romantic partnerships and troubled relationships with his bandmates. But after almost 20 years together in Ismaily’s longest relationship, Ceramic Dog, Ribot sees the need.

“Given the challenges Shazad had growing up and the way he plays rock, this is no coincidence. It’s about facing mortal destiny,” Ribot said in a telephone interview. Told. “He’s the most natural anarchist I’ve ever met, because he has a natural desire to go beyond the limits that stand in his way.”

Ismailies are experts at lending their superpowers to others and reminding them that they have them. Beth Orton recalled the frustrating process of making her 2022 album, Weather Alive, and convinced herself that she no longer belonged in the music industry because of label woes and abandoned sessions. I looked back. But then she started sending demos to Ismaily. Ismaily responded to her uncertain hymn with a throbbing, pre-dawn gut reaction. “I was very depressed, but I think he understood how kind I was,” Orton said in an interview. “I felt like I met a very cold winter.”

But Ismaily still seeks to bring together such audacity in his work. He frequently performs nude shows, including memorable gigs on blazingly hot East River boats and Counting Crows covers at a Brooklyn charity cloaked entirely by acoustic guitars. . These stories stem partly from the temperature problems he would endure for the rest of his life, and partly from confronting the shame of his body that had long caused him sorrow. He admitted that he did.

“I feel ecstasy when those performances are over,” Ismaily said. “It’s the ecstasy of being able to feel who you really are and survive just by showing someone who you really are.”

But he worried that he still lacked the faith—what he called “artistic depth”—that he could immortalize something to his name. For his ten years, he has run his own studio and his record label of the same name. This imprint specializes in the first albums of veteran collaborators, role players and musicians who make celebrity albums even better. Ismaily knows that his portrayal sums up much of his own work. He hopes one day to work up the courage to take that mantle and make his own records for his own label in his own studio.

“It’s crazy that I’m 51 and still have unresolved trauma. That’s why I can’t make records,” he said after nearly five hours of discussing the very trauma. Ismaili, still in good spirits, said. “It feels like a non-climber casually driving past the base of Everest, but the results will be very exciting.”